The large speckled egg lay in the palm of my hand. I had just viewed the contents with the aid of a candling light, and watched the eagle embryo break through the inner membrane and take its first breath of air.

I could feel a slight tightening of my coronary arteries and I became aware that I was taking shallow breaths. This momentary condition came upon me as I dithered with the decision I had made before hand to pierce the shell, allowing a flow of fresh air into the air sac area. There were pro’s and con’s to this action and as I hesitated for a second I could feel a bead of sweat form on my brow. I could feel a slight tightening of my coronary arteries and I became aware that I was taking shallow breaths. This momentary condition came upon me as I dithered with the decision I had made before hand to pierce the shell, allowing a flow of fresh air into the air sac area. There were pro’s and con’s to this action and as I hesitated for a second I could feel a bead of sweat form on my brow.

This Golden Eagle egg was important to me, it was the first of six fertile eggs my female eagle ‘Maria’ had produced through voluntary artificial insemination, which had developed to this advanced stage of incubation.

Our previously successful inseminations had unfortunately resulted in the embryo’s terminating at a very early stage of development. The reasons were speculative, and alterations to the eagles management and methods of incubation had been implemented, in the hope that we could proceed from what was becoming a log jam in the development of a full term embryo.

As I placed the eagle egg back into the hatcher I contemplated the enormous time span and effort it had taken me to arrive at this moment. The next stage would be the pipping of the shell, but for now the embryo should rest. I was delighted that this time we had progressed this far but fearful of ‘counting ones chickens’. At long last it looked as though what had become a lifetimes daydream could actually be achieved.

‘Maria’ my female Golden Eagle was now twenty five years old, together we had traversed the years,  we had hunted the varied terrain of this country and in these latter few years she had concentrated her time in the breeding chamber. we had hunted the varied terrain of this country and in these latter few years she had concentrated her time in the breeding chamber.

‘Maria's’ very existence in captivity was through my early belief that I could breed golden eagles with the aid of voluntary artificial insemination.

Although a quarter of a century ago few raptors had been bred in captivity and virtually all that were used in falconry were wild taken stock, I had embarked on a course to find a female golden eagle for my hunting male eagle ‘Ivan’.

Little or nothing was understood by most falconers as to the complex nature of imprinting, or the social etiquette between falconer and a sexual pair bonded raptor.

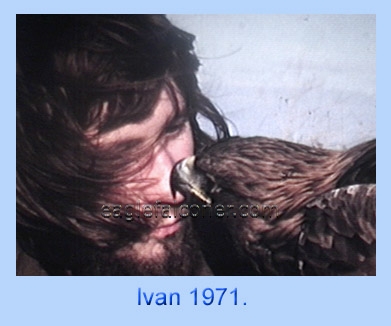

I was unaware that the close hunting relationship that had developed between myself and ‘Ivan’ was intensifying as he progressed into adulthood. I was abruptly brought into the picture one morning as I routinely tethered him to his weathering block. Crouched to tie the leash to the block ring, ‘Ivan’ found the area of my back irresistible. Startled by the eagle landing on my back I instinctively rolled him off, but once having realised he intended no harm I allowed his second attempt to proceed. He balled his feet and attempted to copulate, his early attempts produced no semen but it set me on a course of possibilities.

Sixties Britain held few captive Golden Eagles, and the majority of those were held by zoological collections usually as individual specimens. Falconers with golden eagles were a rare breed, possibly four or five of which two or three were regularly flown at quarry. My attempts to acquire a second eagle were directed towards those zoological collections which showed some interest in the idea of breeding golden eagles.

The first real faith in my belief came from Miss Molly Badham, Director of Twycross Zoo and eminent breeder of endangered primates. Within her collection she had three individual eagles housed in a large flight cage. A Spanish Imperial Eagle, a male Crowned Eagle and a female Golden Eagle. The first real faith in my belief came from Miss Molly Badham, Director of Twycross Zoo and eminent breeder of endangered primates. Within her collection she had three individual eagles housed in a large flight cage. A Spanish Imperial Eagle, a male Crowned Eagle and a female Golden Eagle.

The female Golden Eagle was named ‘Helga’ and had in the past been handled by Lorent de Bastyai when he had worked at the Zoo. She was a fine eagle and Molly was keen to hand her on to me, but in true zoological tradition was also keen to receive a specimen in return to enhance her collection.

My best hope to procure ‘Helga’ was to find a mate for either the Imperial or the Crowned eagle. As I was in touch with nearly every eagle owner in the country my only hope seemed to be in the pairing of the Crowned Eagle. I was corresponding with David Ried-Henry the artist who owned a female Crowned Eagle, ‘Tiara’. David had had this eagle since she was four months old and had flown her successfully at quarry. , now twelve years old and laying eggs she was becoming belligerent and doing her best at putting David in hospital at every opportunity. I knew he was contemplating returning to Africa and releasing ‘Tiara’ back to the wild, but would he consider her for an attempted breeding project ?.

Although I presented a passionate request he was so against raptors being housed in aviaries and felt it total waste of raptor life to cage two birds in the vain attempt of breeding them. He was convinced ‘Tiara’ would smash her face in the wire and pursue the male until she killed him. To be fair, with the knowledge of breeding raptors at that time this was probably an accurate scenario, and so went the possibility of my obtaining ‘Helga’.

The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland housed two female Golden Eagles at their Edinburgh Zoo. ‘Benim’ a young adult female, was housed in the tall telegraph pole rock faced enclosure. In a smaller enclosure there was a pale coloured adult female from “off the hill”.

She had been picked up in the highlands, suspected as suffering from the effects of poison and sent to the zoo for care. Her six month stay in captivity had seen her condition improve, she was very calm and had a tranquil effect on me as I gazed into her pale eyes trying to imagine what she made of this busy zoo life.

I spent many hours over numerous journeys to the Zoo discussing my ideas of breeding eagles with the new Director Roger Wheater. My proposal would have to be put forward to the Animal Management Committee for approval. The waiting for a decision seemed to take an age, but to my surprise they approved the transfer of the wild adult female to me. I had not even considered her, firstly thinking because she was an adult wild eagle temporarily incapacitated, and would naturally be released once fit. It was ‘Benim’ an eagle who had been in captivity since leaving the eyrie that I thought most suitable, but the committee felt as ‘Benim’ was well adapted to captivity she should continue as their main display eagle.

By now I was desperate to obtain a female eagle, and logic seemed to evade me, I would settle for this eagle, who knows maybe she would cooperate with me. Things move slowly within large organisations, and I was not famed for my patience indulgence to a lack of progress. My nail biting wait abruptly ended with the receipt of a letter from the Society informing me of the death of the female eagle just days before she was to be boxed and shipped to me. To make matters worse Zoo officials had apprehended two young boys within the grounds brandishing an air rifle on the day of the eagles death.

It was a hard enough blow to bare to loose the eagle I had worked so hard to acquire, but to have it shot was such a senseless waste. As it transpired, the post mortem result exonerated the young boys of such a deed, the eagles death was due to long term liver damage due to the effects of poison. A sad end to such a fine proud bird and a dead end to my attempts to obtain an eagle for breeding. I felt I had come to the end of the road, I had tried all of the options I could think of. I had been given a great deal of encouragement, in fact I think I had inspired one or two individuals to think that my idea of breeding eagles was maybe possible. Still, the end result of all this effort was zero, I was no closer than when I set out..

As the hunting season of 1972/73 came to a close I put ‘Ivan’ ready for the moult, his amorous intentions with me highlighted my inadequacy. As the hunting season of 1972/73 came to a close I put ‘Ivan’ ready for the moult, his amorous intentions with me highlighted my inadequacy.

I had all but given up on my notion of breeding eagles when in early May I received a letter from a Mr. Welsh, Assistant Secretary at the Scottish Home and Health Department. The letter instructed me that the Department had been informed of the zoo eagles death and a license was enclosed to permit me to take a wild born eaglet from an eyrie in Scotland. A license granted in early May gave me little time to organise. It stipulated that I could take an eaglet from the counties of Inverness-shire and Argyll. These counties cover a vast area of the Scottish Highlands containing many eagle eyries. I had some contacts that knew the mountains and the locations of many eyries, with some judicial arrangements of worktime I was able to travel North on a couple of scouting trips to locate viable eyries in the highlands.

This license was only the second ever granted and the first for a breeding purpose. At the time we were treading a new course, no one knew how many eagle licenses would be granted in the future, or for how long license allocation would continue. I made an unofficial agreement with the advisory committee that I would only take an eaglet from a twin eaglet eyrie. Thus reducing the risk of the parent eagles deserting that eyrie due to a failed breeding season, as they surely would if a single eaglet was taken.

This put an extra pressure on me to find a suitable twin eaglet eyrie, in an accessible location which made removal of the eaglet reasonable possible.

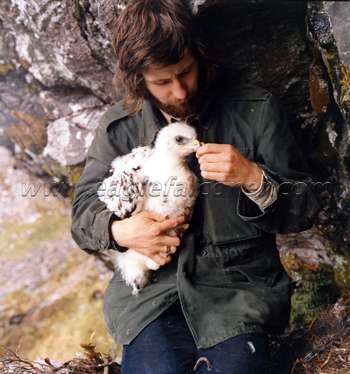

On the 2nd June 1973 I came face to face with Maria and her brother, she was a big downey just ready to stand and weighed 8lbs.

At last I had a pair of Golden Eagles, but the reality of breeding eagles was a long way ahead. ‘ Maria’ had at least four years before she was sexually mature enough to lay eggs. In that time I had to establish a pair bond with her as every bit as strong as the bond between ‘Ivan’ and I.

The only way I understood to form such a bond was to fly this female eagle, she had grown into a large powerful hunting raptor and it took fourteen years before she turned her amorous attentions towards me. Sadly in that time ‘Ivan’ had died and I had shelved the notion of breeding eagles.

Once again I needed another eagle, although this time the breeding of raptors in captivity was no longer a vision of the few it was a massive reality. Strident, innovative advances had been developed by falconers in the highly successful propagation of many species of raptors. This time initially I sort the help of fellow eagle falconers who had imprinted adult male eagles, with the intention of obtaining viable semen. In the following few years ‘Maria’ built and rebuilt her large eyrie and laid, incubated and foster reared a number of buteo eyases. What I was unsuccessful in obtaining was the elusive viable semen, those who had seen their males give semen could never produce such a product when required. Once again I needed another eagle, although this time the breeding of raptors in captivity was no longer a vision of the few it was a massive reality. Strident, innovative advances had been developed by falconers in the highly successful propagation of many species of raptors. This time initially I sort the help of fellow eagle falconers who had imprinted adult male eagles, with the intention of obtaining viable semen. In the following few years ‘Maria’ built and rebuilt her large eyrie and laid, incubated and foster reared a number of buteo eyases. What I was unsuccessful in obtaining was the elusive viable semen, those who had seen their males give semen could never produce such a product when required.

Finally, yet again to my rescue came the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, this time they had five eagles in their collection. They had a male called ‘Edward’ who was seventeen years old and had been in captivity since leaving the eyrie. He had been housed with a number of females during his time in captivity, but had not formed a bond with any of them. It was felt that he may be imprinted enough to become a viable semen donor and so he was offered to me.

‘Edward’ bonded within weeks, but it was five years before he gave viable semen and in that year we produced our first fertile Golden Eagle egg. The embryo died within the first week of incubation, and at first I believed ‘Maria’ had possible let it chill. The following two years I managed two fertile eggs each year, but regardless of my strident improvements in incubation methods my end results were the same.

In desperation I prepared for an extreme method of management, I had naturally fed a varied diet,  mostly hope grown quail, rabbit and wild rifle shot rabbit. In addition I had added Vitamin and mineral supplement plus pro-biotic and Vitamin E, the main diet was stored deep frozen and freshly thawed with a small proportion freshly killed and fed warm. mostly hope grown quail, rabbit and wild rifle shot rabbit. In addition I had added Vitamin and mineral supplement plus pro-biotic and Vitamin E, the main diet was stored deep frozen and freshly thawed with a small proportion freshly killed and fed warm.

Throughout the winter of 97/98 and up to the end of egg laying I fed both eagles nothing but freshly killed warm food, no additives. All eggs were naturally incubated under ‘Gloria’ my totally reliable buff Cochin hen. Only one egg was found to be fertile, and ‘Gloria’ dutifully sat for twenty three hours per day.

During her two half hour breaks the fertile egg was removed to a incubator running at one degree less than incubation temperature, it was never allowed to cool. The embryo thrived throughout those forty long days, and burst into the air sac bang on schedule.

It took sixty two and a quarter tortiously marvellous hours for the embryo to break free of the shell, as I iodined its umbilicus it was hard to imagine the miraculous transformation that would develop over the coming weeks. Three and a half hours later I moved the eaglet to the brooder, its down was still not dry and fluffy. Three and a half hours after that it took two small pieces of quail heart, and so started a regime of four daily feeds which rapidly transformed this helpless little scrap. Within a week it had doubled its hatched weight and by day eleven I handed a 220 gram determined bundle of an eaglet into ‘'Maria's'’ care. It took sixty two and a quarter tortiously marvellous hours for the embryo to break free of the shell, as I iodined its umbilicus it was hard to imagine the miraculous transformation that would develop over the coming weeks. Three and a half hours later I moved the eaglet to the brooder, its down was still not dry and fluffy. Three and a half hours after that it took two small pieces of quail heart, and so started a regime of four daily feeds which rapidly transformed this helpless little scrap. Within a week it had doubled its hatched weight and by day eleven I handed a 220 gram determined bundle of an eaglet into ‘'Maria's'’ care.

This was the big one for ‘Maria’, she had been practicing for many years with experimental foster eyases waiting for this moment. I had enormous confidence in her, but all the same I stayed with them both to observe all went well.

Her dedication, patience and delicate manoeuvring around such a helpless ball of fluff is an amazing experience to watch at such close quarters.

Over the next couple of weeks my role was reduced to food provider and family album photographer. One day twenty four the eaglet was standing in the eyrie and the following day I fitted the DOE closed ring, reporting in my daily log that growth was so rapid that the following day may well have been to late to get the ring to fit.

My intentions had been to remove the eaglet from ‘Maria’ for social imprinting, once it was able to feed itself. But events have a way of presenting themselves which don’t always follow to plan. ‘Maria‘ was very relaxed with me handling the eaglet and clambering about in the eyrie, so I decided to remove the eaglet on a part time daily basis.

Each morning I would climb into the eyrie with a large plastic box in which to transport the eaglet with me to my workplace. I am lucky enough to work within a small factory environment that is relaxed enough, to allow the social imprinting of as large a raptor as a golden eaglet. At lunch time I would return the eaglet to the eyrie, upon which ‘Maria’ would immediately fly in and feed the eaglet. This routine worked exceptionally well and by day thirty six the eaglets weight of five pounds eleven ounces confirmed to me, it was a male.

‘G’Kar’, is a warrior, an honourable character from a fictional SiFi TV series. I chose this name for my young eaglet as it phonetically appealed to me. I had come full circle and once again I would fly a male Golden Eagle, but this time he was Home Made.

|