Growing up on my native Island of Jersey, my early memories between the age of eight to twelve years were probably heavily influenced by my first real hero. Growing up on my native Island of Jersey, my early memories between the age of eight to twelve years were probably heavily influenced by my first real hero.

Roderick Dobson’s writing in the ‘Birds of the Channel Islands’ stirred my young blood as I scoured the island for a sighting or nest site of the numerous resident avain species.

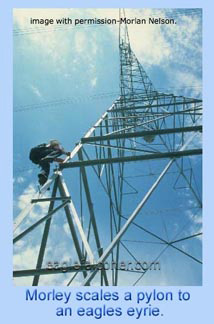

I know I caused my parents many anxious hours on the many occasions I was missing from home, only to be found scrambling on the notoriously dangerous island sea cliffs looking for nests.

As my interests progressed to falconry and my life was enveloped by its fascination, I found and met a handful of individuals along the way, who's knowledge, understanding and compassion for the art of falconry, strongly influenced and greatly added to my enjoyment of the art.

Some years ago I made a pact with myself to seek out and correspond with as many dedicated  falconers as I could, the sort of falconer to whom it was not a mere sport, but a way of life, a passion, a philosophy. falconers as I could, the sort of falconer to whom it was not a mere sport, but a way of life, a passion, a philosophy.

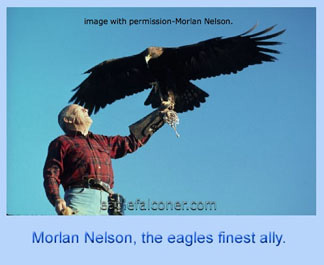

To this end, for the past few years I have been enjoying an extended correspondence with Morlan Nelson, one of Americas great ambassadors for the right of birds of prey to fly in the skies, without every rancher and landowner reaching for a gun. To this end, for the past few years I have been enjoying an extended correspondence with Morlan Nelson, one of Americas great ambassadors for the right of birds of prey to fly in the skies, without every rancher and landowner reaching for a gun.

It was Morlan’s work with eagles that first inspired my initial correspondence, but it soon became evident to me that Morley Nelson and I would have to sit down and just talk eagles and falconry face to face.

What started as casual planning soon gathered momentum, and before I knew it I was standing in the foyer of Boise airport U.S.A. It was early evening but I was feeling the effect of loosing seven hours, and my body demanded a bed after twenty three hours travelling.

When I had first arrived in Boise. I telephoned Morlan Nelson to arrange my schedule, he suggested that I look in at the World Center for Birds of Prey first, to see the showcase that is dedicated to some of his life. This I duly did as part of the official tour of its ‘Interpretive Center’. On display was Morlan’s first conservation tool, his holstered hand gun. Returning from the War Morlan continued to fly falcons and make 8mm films of them, but so many people stopped to shoot at his falcon if it landed on a power pole that he started to carry a Colt frontier model six gun to fire in their direction if they attempted to shoot at his falcon.

This wild west action saved many of his falcons lives but it nearly started a war in the state of Utah where he lived. So many individuals believed that all chicken hawks, bullet hawks and duck hawks  should be shot on sight, and this caused many a heated argument which nearly ended in a shoot out. It became clear to Morlan that the way forward was through education not the bullet. should be shot on sight, and this caused many a heated argument which nearly ended in a shoot out. It became clear to Morlan that the way forward was through education not the bullet.

Walt Disney, having seen Morlan’s early 8mm movies of his falcons brought him to Hollywood as a consultant on early wildlife adventures as The Living Desert and The Vanishing Prairie . Morlan flew Red tail hawks and Prairie Falcons, which gave many Americans their first intimate sight of wild birds of prey. The effects of the Disney films and the six series of TV’s “Wild Kingdom” which Morlan worked on had such a dramatic effect on the American public perception of wild birds of prey, now you hardly ever hear the words, “chicken hawk” used.

Also on show were Morlan's war medals, he had given them to the Center as he felt that their possession by him was morally wrong and they should have been awarded to his fallen comrades. As an officer in the legendary Tenth Mountain Division, the all-volunteer ski troops, Morlan saw action from the Aleutians to the Battle of Brenner Pass. Also on show were Morlan's war medals, he had given them to the Center as he felt that their possession by him was morally wrong and they should have been awarded to his fallen comrades. As an officer in the legendary Tenth Mountain Division, the all-volunteer ski troops, Morlan saw action from the Aleutians to the Battle of Brenner Pass.

Decorated with the Silver Star and Purple Heart and wounded in the final week of hostility, but languishing in a hospital bed with his leg in a cast was not to stop Morlan from a successful attempt to obtain a young kestrel he had been watching on a nearby cliff. It involved rappelling down a cliff, but he returned to the hospital with the kestrel, a broken cast and some unexplained rope burns on his pyjamas.

I was beginning to understand the enormity of the task ahead of me in trying to document much of Morlan Nelson’s life. His long life right from a boy growing up on a North Dakota ranch has been dedicated to the education of the American people towards the conservation of its birds of prey.

My real interest in Morlan Nelson was his work with eagles, and predominately the Golden Eagle. Although Morlan has worked with Bald, Bateleur and Harpy eagles, it is his work with golden eagles which is so extensive and of such great interest to me.

We talked for days, and Morlan demonstrated many of his technics often  using his female golden eagle to model a particular hood or to show me how he applied the snap fit jesses he developed for his film work. using his female golden eagle to model a particular hood or to show me how he applied the snap fit jesses he developed for his film work.

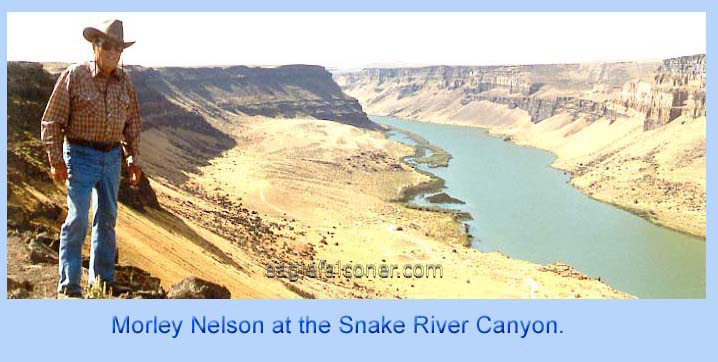

Not all of our discussions were of the armchair variety, Morlan enthusiastically guided me on trips to the Boise River Canyon and the famous Snake River Canyon.

The night before our planned trip to the Snake River Canyon, Morlan announced that he would take a rope along, so we could go over the edge and I could have a better view point for photographing the canyon.

WE could go over the edge of the canyon, never one to make much of a point as to how much of a wimp this Englishman might be, I kept my mouth shut. This coupled with the loose talk of sun basking diamond backed rattlesnakes, had the effect of concentrating the mind. If fact I was conscious of where I was placing my feet in this hot arid dessert landscape, I had no intention of disturbing the slumbers of any ten foot diamond back, No siree.

As we walked, Morlan pointed out many new and disused eyries of Golden Eagles and Prairie Falcons, in this remote and desolate canyon which at first glance is like many desert, river and cliff complexes in the North Western United States. It was not until Morlan Nelson moved to live in Boise, Idaho that he discovered that the Swan Falls area of the Snake River to be a very unique habitat, probably in the United States if not in the world.

It was though Morlan's work as a soil scientist and hydrologist employed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Soil Conservation Service, that he discovered the condition of the top soil surrounding the top of the canyon. This deep, medium textured soil was perfect for the burrows of the Townsend ground squirrel who multiplied in the area in large numbers.

Morlan also discovered that up to ten per cent of the nesting prairie falcons in the United States live in this unique 33 mile stretch of the Snake River Canyon, and that the Townsend ground squirrel made up to 70 per cent of the falcons diet.

Forty nine pairs of prairie falcons nested in the Swan Falls area, which means there was a falcons nest every 300-400 yards in the canyon. Morlan also found that this area of South Western Idaho contained about 100 Golden Eagle eyrie's, probably the largest concentration in North America and possible the world. Forty nine pairs of prairie falcons nested in the Swan Falls area, which means there was a falcons nest every 300-400 yards in the canyon. Morlan also found that this area of South Western Idaho contained about 100 Golden Eagle eyrie's, probably the largest concentration in North America and possible the world.

He brought this unique location into the living rooms of millions of Americans through two nationally televised films that he worked on, Disney’s “Ida the Off-Beat Eagle” and the Wild Kingdom series, “The Valley of the Eagles”.

Through an enormous amount of lobbying, Morlan brought the uniqueness of this priceless heritage to the attention of the Department of the Interior, and upon the recommendation of the Bureau of Land Management, a protective withdrawal of 26,255 acres of land along the Swan Falls reach of the river was designated a “Nature Area” a unique and exceptional sanctuary for rare birds of prey, now known as the Snake River Birds of Prey Natural Area.

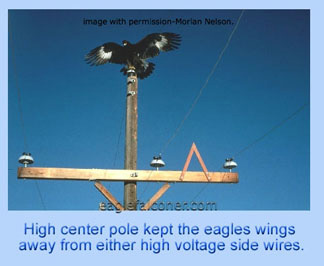

In April of 1972, a new effort to increase consideration for eagles was spearheaded by the Idaho Power Company. It had found a problem with eagle electrocutions, the eagles often use power poles as landing sites from which to scan the surrounding terrain for game. A wingspan from six to eight feet makes it easy for a landing eagle to simultaneously touch the two phase conductors ( or one phase conductor and a ground wire) on either end of the crossarm.

More and more eagles were being found under the company’s power lines, victims not only of the electricity but of gunshots, poison and starvation. Although the power company was unable to do anything about the last three things, it felt it might be able to prevent the electrocutions, but it wasn't sure how.

Morlan Nelson now recognised as one of the world’s foremost authorities on eagles, hawks and other birds of prey was enlisted to help with Idaho Power engineers and biologists to study the problem of eagles and power lines.

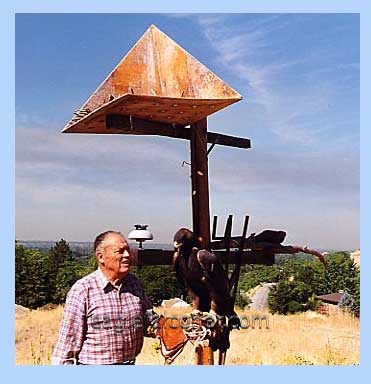

Idaho Power line crews built mock-ups of various types of poles in Nelson’s backyard in the foothills  near Boise so he could study the eagles behaviour around the poles. Using his skills as a cinematographer, Morlan Nelson spent hundreds of hours filming his trained eagles in 16mm slow motion on the mock-ups. The big birds were tested in a variety of wind conditions and the films provided dramatic proof of an eagle’s ability to touch both conductors with its wing tips. near Boise so he could study the eagles behaviour around the poles. Using his skills as a cinematographer, Morlan Nelson spent hundreds of hours filming his trained eagles in 16mm slow motion on the mock-ups. The big birds were tested in a variety of wind conditions and the films provided dramatic proof of an eagle’s ability to touch both conductors with its wing tips.

A study of Idaho power pole landing sites determined that 95% of the electrocutions could be prevented by correcting 2% to 15% of the poles. This is due to the eagle’s extreme selectivity in choosing a landing site. Prevailing winds, prey density and surrounding topography have to be exactly right.

The corrections made by the Idaho Power Company varied from covering conductors and raising one wire to building perches on top of the poles.

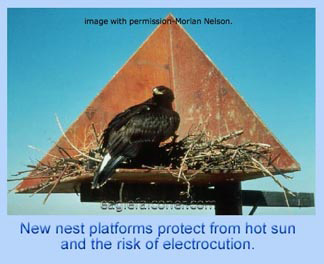

The sometimes fatal attraction of some species of birds of prey to nesting on power structures carrying 69,000 volts resulted in the Idaho Power Company’s cooperation in designing nesting platforms for the larger birds , especially eagles.

The idea for this platform came when Nelson observed a pair of golden eagles nesting on the observation tower from which the Idaho Air National Guard marks bomb hits from fighter planes in training pilots.

The tower was an ideal nest, providing shade, elevation and protection from the wind. The nesting platform is mounted on a power structure, the open or unshaded end must be away from the tower. This gives the adults maximum freedom to land under all wind conditions.

The Company stipulated that these nesting platforms should be constructed of materials impervious to weathering and have a projected lifespan equal to that of th He power pole- approximately 100 years. Sturdy, permanent structures would not only minimise maintenance and replacement costs but would be of greater advantage to the birds.

The success of these corrective modifications was documented in slow-motion photography. After correction, the poles became positive ecological factors rather than inviting, but lethal killers.

It has been estimated that the work done to the Idaho Power Company’s poles following Morlan Nelson’s advice, which has been copied by other power companies within the western US, has saved the lives of around 300 eagles each year.

The work on the power line problem lasted over a decade and Morlan’s own film company ‘Tundra Films’, filmed and produced the award winning film “Silver Wires, Golden Wings” which won top honours in four national film festivals.

Nelson’s work on the thousands of modified power poles and nest platforms have actually benefited the eagles and other raptors. While there’s a solid prey base for raptors in the treeless high deserts of the western United Sates, high places which can be used for nest building and hunting perches are scarce. The building of power lines across the nation has undoubtedly helped raptors to increase their geographic distribution.

With a life time dedicated to the promotion of the protection and better understanding of birds of prey, Morlan Nelson is The Man who saved the Eagles.

When the time came for our goodbyes, it was a tough parting, I just wanted to stay a few more days. As Morlan put it, ‘We are looking at things from the same track, Al.’, all I can say is, ‘it is a pleasure and an honour to know you Morlan Nelson, you are one of my personal heroes’. |